ABDOMINAL AORTIC ANEURYSMS (AAA)

vascular.co.nz>abdominal aortic aneurysms

What is an abdominal aortic aneurysm?

Are aortic aneurysms common?

Why do aortic aneurysms develop?

Why are aortic aneurysms important?

Can aortic aneurysms be prevented?

How will I know if have an

aortic aneurysm?

When do

aortic aneurysms require treatment?

Thoracoabdominal aneurysms

What treatments are

available for aortic aneurysms?

What are the complications of

aortic aneurysm treatment?

What measures are

taken to reduce complications?

Aortic aneurysm screening programmes

Aortic Aneurysm

references

Aortic aneurysm links

What is an abdominal aortic aneurysm?

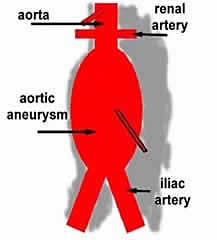

An

aneurysm is a swelling or dilatation in a blood vessel. Aneurysms can occur in any blood vessel, but are much more common in arteries,

although they do occur rarely in veins. An abdominal aortic aneurysm

(AAA) is a

dilatation in the abdominal (tummy) part of a major artery - the aorta. This is

one of the commonest types of aneurysm.

An

aneurysm is a swelling or dilatation in a blood vessel. Aneurysms can occur in any blood vessel, but are much more common in arteries,

although they do occur rarely in veins. An abdominal aortic aneurysm

(AAA) is a

dilatation in the abdominal (tummy) part of a major artery - the aorta. This is

one of the commonest types of aneurysm.

Aortic aneurysms are fairly common especially in older men. Hospital admission rates for aneurysms also appear to be increasing (Filipovic M et al, 2005). About 6% of men (6 in 100) aged 80 years will have an aneurysm (Bengtsson H et al, 1992). They account for 1.4% of deaths in men over the age of 65 years and 0.5% of deaths in women. ABout 6000 people die in the UK from a ruptured aortic aneurysm each year (Sayers RD, 2002). They are more common in brothers and there is an increased risk of an aortic aneurysm if you suffer from high blood pressure or atherosclerosis (hardening of the arteries).

Aortic aneurysms seem to be relatively rare in Asian populations. The Maori population in New Zealand has a higher death rate from aneurysms (8.9 per 100,000 in Maori vs 3.7 per 100,000 in non-Maori) and require more emergency operations than the non-Maori population, despite a slightly lower age-adjusted admission rate (12 per 100,000 vs 15 per 100,000, Rosaak JI et al, 2003).

Why do aortic aneurysms develop?

We do not know exactly why some people develop aortic aneurysms. They are much more common in men and may sometimes run in the family. There seems to be an approximate four times increased risk of having an aneurysm for the brother of a patient with an aneurysm. Stated another way the brother of a patient with an aneurysm has about a 10-15% chance of developing an aneurysm. Most brothers (more than 80%) will not develop an aneurysm. Surprisingly, the presence of diabetes seems to have a slight protective effect on aneurysm development

Aneurysms may develop because of a weakness in the tissues holding the blood vessels together or possibly an imbalance in various enzymes (matrix metallo-proteinases or MMPs) that are found in the blood vessel wall. No specific genes have yet been identified in relation to aneurysms (Powell JT, 2003).

Why are aortic aneurysms important?

Aortic aneurysms are important because sometimes they can burst. When an aortic aneurysm bursts it is a catastrophic event in which the patient can die from internal bleeding in a matter of minutes. In most people a burst (ruptured) aortic aneurysm is fatal.

The risk of an aneurysm rupturing varies with the aneurysm size. The larger the aortic aneurysm the more risk of it rupturing. Small aneurysms less than 5.5cms in diameter have an annual risk of rupture of less than 1% (1 in 100). This means that a patient, with an aortic aneurysm less than 5.5cms in diameter, has approximately a 1 in 100 chance of it bursting over the next 12 months.

A recent Canadian study has reported specific figures for the risk of rupture based on aneurysm size (Brown PM et al 2003). For men the annual risk of an aneurysm rupturing was 1-1.8% for aneurysms between 5.0 and 5.9cms, but increased to 14.1-15.6% when the aneurysm was 6cms or greater. In other words a man with a 5.4cms diameter aneurysm has only 1 or 2 chances in a hundred that his aneurysm will rupture in the next year. Once the aneurysm increases to 6.1cms that risk will increase to approximately 15 chances in a hundred. In women the risks are greater. A woman with an aneurysm between 5.0 and 5.9 cms has a 3.9 - 4.7% risk of rupture over the next year. Once the aneurysm size increases beyond 6.0 cms the risk of rupture increases to 22 - 30% over the next year.

Less commonly aortic aneurysms can cause other symptoms. The aneurysm is usually lined by blood clot, which in most people, is not dangerous. Occasionally, parts of this blood clot can be dislodged and travel downwards to block arteries to the leg (embolism). As the aneurysm enlarges it can cause pressure on nerves and can occasionally lead to pressure on the ureter (the tube between the kidney and bladder). This can prevent urine draining from the kidneys normally and the kidneys can become damaged.

Repair of an aortic aneurysm will stop these complications developing.

Can aortic aneurysms be prevented?

At present aortic aneurysms cannot be prevented from developing, but their growth may be slowed by some simple measures. If you smoke, this increases the rate of growth of aortic aneurysms and you should stop immediately. Your blood pressure should be checked and if it is persistently raised you should have treatment to reduce your blood pressure. High blood pressure is a risk factor for aneurysm rupture. This does not mean your aortic aneurysm will rupture if you have high blood pressure, but it does place it at slightly higher risk of rupture.

It is important to have your risk factors for hardening of the arteries monitored and treated if necessary as there is a clear increased risk of death even after the aneurysm has been treated due to cardiovascular disease (UK Small aneurysm Trial Participants, 2007). There is some evidence that cholesterol lowering drugs such as simvastatin, decrease the growth rate of aneurysms (Schlosser et al 2008).

How will I know if have an aortic aneurysm?

Unfortunately, many people will not know if they have an aortic aneurysm, because they rarely cause symptoms until they burst. Aortic aneurysms are sometimes found during a routine examination for other conditions such as prostate problems or gallstones. If you are a man over the age of 60 years, a smoker with high blood pressure and have a brother or father with an aortic aneurysm, then this puts you at increased risk. If you also have hardening of the arteries at other sites (eg previous stroke or heart attack) then you may also be at increased risk.

Although examination by your doctor may be helpful in diagnosing a large aortic aneurysm, it is not a sensitive method of diagnosing smaller aneurysms. The best way to diagnose an aneurysm is with an ultrasound scan of the abdomen. This is a very quick, simple, accurate and safe test that is also commonly used to examine babies in the womb.

Occasionally, patients experience abdominal (tummy) and back pain and the aneurysm becomes tender before it ruptures. If this happens and you know you have an aneurysm, then it is important to seek emergency medical advice.

Before surgery most patients will undergo CT (computed tomography) scanning to show the aneurysm in more detail. The picture below is a CT scan of an aneurysm. This picture represents a slice across the abdomen. The spinal column is shown at the back.

White arrow points to aneurysm

T is thrombus or blood clot inside the enlarged artery

L is the lumen or part of the artery where blood is flowing.

IVC is inferior vena cava or the main vein in the abdomen.

When do aortic aneurysms require treatment?

The aorta - the main blood vessel that becomes swollen - is usually about 2.0-2.5 cms in diameter although this can vary with age and whether you are a man or a woman. We know from two large studies in the USA and UK (Lederle FA et al 2002, ) that aneurysms less than 5.5 cms across can be safely watched as long as they are monitored on a regular basis. For aneurysms less than 4.4 cms across or less, a yearly ultrasound scan is sufficient to monitor aneurysm growth. For aneurysms between 4.5 and 4.9 cms across, a scan every 6 months is advised. An aneurysm greater than 5.0 cms across requires scans every 3 months.

When an aneurysm reaches 5.5 cms most surgeons would consider offering surgical intervention. This is because, at this size, the aneurysm has a greater risk of rupture. It then becomes as safe to have an operation to repair the aneurysm, as it is to leave the aneurysm alone. Surgery may also be considered if your aneurysm is rapidly expanding on regular scans or it starts to cause other complications (see above). Rapid expansion means more than 7mm in 6 months or 1.0cms in one year. Whether you proceed with surgery will not just depend on the size of the aneurysm. It is important that each patient is fit enough to withstand the operation. Fitness for surgery can be affected by many factors and the decision whether or not to proceed with surgery can be a difficult one, as it is a very major operation. It will only be after a detailed discussion with your surgeon, regarding your own personal circumstances and type of treatment available, that a decision can be reached.

There is still some debate on the treatment of aneurysms between 4.0 and 5.5cms despite the large UK and North American trials indicating that there is no clear benefit. Looked at in another way though, there was no clear disadvantage to having the aneurysm treated at an earlier stage. Overall 60% of all patients in the trial would eventually require an operation so why not step in at an earlier stage? Taking patients with aneurysms over 5.0cms the argument is even more convincing, as over 80% of these patients eventually require surgery. Despite this the accepted cutoff to initiate treatment is still 5.5cms. Endovascular treatment of aneurysms (see below) has lower operative mortality than open surgery and it has been proposed that treating smaller aneurysms with stents will lead to benefits. The PIVOTAL and CAESAR trials shouls shed some more light on this important area.

If your aneurysm bursts it usually causes severe back and abdominal pain. The bleeding can stop temporarily in some patients and in these patients an emergency operation can be successful at repairing the aneurysm. The majority of patients (>70-80%) with a ruptured abdominal aneurysm will not survive.

It is important to remember that although any anxiety you may have had about your aortic aneurysm will be relieved by having it repaired, the operation will not make you feel physically better. This is because most patients do not have symptoms from their aneurysm before the operation. The operation is a treatment to prevent the aneurysm rupturing or causing other complications in the future.

Most aortic aneurysms are found below the arteries to the kidneys (renal arteries) in the abdomen Some aneurysms can extend upwards to involve the arteries to the kidneys, the arteries to the intestines, liver and stomach. More extensive aneurysms will involve the aorta from where it leaves the heart and can extend throughout the chest. These aneurysms are much more difficult to repair and carry much greater risks from treatment. Open surgery for these aneurysms is massive surgery, but until recently was the only treatment available. Newer endovascular treatments are revolutionising therapy in patients with these aneurysms and extending the treatment to patients who previously would have been considered unfit for open repair. This is a rapidly developing area with different devices and different combinations of treatments being explored.What treatments are available for aortic aneurysms?

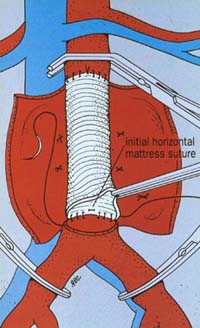

Open Surgery

The traditional treatment for aneurysms is surgery to replace the diseased blood

vessel with an artificial blood vessel (graft). In the conventional open operation

a large incision is made in the abdomen. The blood vessels above and below

the aneurysm are clamped in order to control any bleeding and the aneurysm

itself is opened. Any blood clot in the aneurysm is removed and any

bleeding blood vessels are controlled. The artificial graft is then

stitched into place using permanent stitches. The graft is made from a

man-made material called Dacron, similar to Terylene.

This is a major operation requiring 7-10 days in hospital and usually a short post-operative stay on the intensive care unit. If you have this operation as a planned procedure there is an overall risk of dying of around 5%. This means that 95 patients out of every 100 will be fine and come through the operation. However, a small number of patients (approximately 5 in 100) will die in hospital either during or more commonly after their operation. These are average results when looked at overall on a country wide basis, although some individual units may claim better survival figures. It is important to remember that your chances of surviving a planned operation are much better than if your aneurysm ruptures, when the overall chance of dying is around 80%. This means that 80 patients out of every 100 who have a ruptured aneurysm will die.

The conventional open operation has a history dating back over 55 years and is a very effective and durable treatment for aneurysms. Once patients have recovered from the operation they rarely have further problems.

Endovascular stenting

Over the last 18 years a new treatment has become available (Endovascular

Aneurysm Repair or EVAR). This procedure is different from the

conventional operation because it does not usually require any cuts in the

tummy. Two small vertical cuts are made in the groin and an artificial

graft (tailored individually for

each aortic aneurysm) is delivered to and deployed from inside the aneurysm itself. This operation

requires a special delivery device to deliver the graft through the

arteries to the aneurysm. At least 16 different delivery devices have been developed to facilitate this procedure and it is likely that major

advances in delivery systems will continue to simplify the operation. Click HERE to view a simulation of endovascular stent placement. EVAR is a rapidly developing field.

The stenting operation is only suitable for patients with certain shapes (morphology) of aortic aneurysm. The number of patients suitable for EVAR varies to some extent on the expertise of the local unit. Only about 50-60% of aneurysms will be suitable for the endovascular technique, but it has the attraction of being much less traumatic than the open procedure. As modern generation devices are refined, more and more aneurysms are becoming suitable for the endovascular technique. Recovery is faster for most people and it may permit much earlier discharge from hospital. More and more complex graft stents are being developed which will deal not only with abdominal aneurysms but also with complex aortic arch and thoacoabdominal aneurysms involving major branches of the aorta. An endovascular graft can be constructed with branches to supply major arterial vessels (branched graft) or holes (fenestrations) can be created in the side of the graft so a stent can be inserted into the branch (fenestrated graft). This is expanding the population suitable for aneurysm treatment as previously only relatively fit patients could withstand the major surgery involved in repair of complex thoracoabdominal aneurysms.

There are two major studies (the Dutch Randomised Endovascular Aneurysm Management (DREAM) trial and the Endovascular Aneurysm Repair Trial-1 (EVAR-1)) that have reported on the endovascular treatment of infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysms (the commonest aneurysms). These trials have rigorous trial designs and protocols that have demonstrated significant improvements in 30 day mortality in patients undergoing endovascular repair (Prinsen M et al, 2004; Greenhalgh RM et al, 2004) when compared with traditional open repair for abdominal aortic aneurysms.

In the DREAM trial the risk of dying from open surgery was reduced from 4.6% to 1.2% with endovascular stenting at 30 days after operation. EVAR-1 showed a similar reduction in 30 day operative mortality from 4.7% with open repair to 1.7% with endovascular repair. By 1 year after surgery this benefit had disappeared in the DREAM trial patients (Blankensteijn JD et al, 2005). At two years the survival rates were 89.6% in the open surgery patients and 89.7% in the endovascular repair group. The initial advantage of having an endovascular repair only seemed to last for a short period (months) around the time of the operation and was then lost. Follow up data (EVAR Trial Investigators 2010, De Bruin JL et al 2010, EVAR Trial Participants 2005) have confirmed that the initial survival advantage for endovascular repair is not maintained and longer term survival is just as likely with open surgical repair. It may be that open repair precipitates death in some of the more fragile patients who may only have a limited life expectancy because of other serious illnesses. There is also some evidence that kidney function may deteriorate more quickly after EVAR.

EVAR-2 (EVAR Trial Participants, 2005, 2010) was a UK study which compared best medical treatment for patients with aortic aneurysms against endovascular repair. This study looked at patients who were not fit for open surgery. After 6-8 years of follow up the overall mortality rates were high at 73% (145 of 197) of patients who underwent endovascular repair and 77% for patients treated medically. This was not a statistically different result and the authors conclude that there is no benefit in having aneurysm treatment, even with the less traumatic endovascular technique if patients have other significant illnesses that preclude open repair. The difficulty here is defining what constitutes significant illness and this will definitely vary between different surgeons. For patients at higher risk careful thought on each individual's risk/benefit from treatment will be helpful.

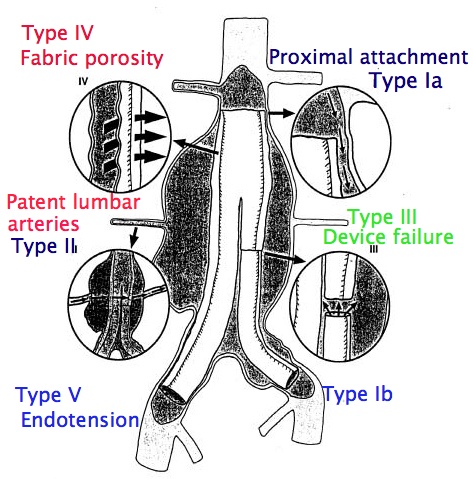

Despite the benefits clearly demonstrated on early mortality with endovascular repair, there are still two major unresolved issues. They are the durability of the procedure and the problem of endoleak.

Endoleak is only a problem in patients undergoing endovascular repair. It occurs when the seal between the graft and the normal arterial wall or between two segments of graft is incomplete (see diagram below (Type I - V endoleaks). If the seal is not complete blood can leak through the seal and fill the aneurysm as it did before the operation. There are also other types of endoleak in which small arterial branches of the aneurysm continue to fill the aneurysm sac. If endoleaks are significant and cause pressurisation of the partly excluded sac (endotension) this can lead to aneurysm rupture - the very thing surgeons are trying to prevent. The EVAR and DREAM trials were initiated many years ago and complication rates may not reflect current practice. There are also varying estimates of the risk of reintervention, but the most reliable results will be from the trials. EVAR-1 showed the risk of complications developing over 6-8 years was 45% (282 of 626) in the endovascular group versus 13% (78 of 626) in the open repair group. Around 20-30% of patients (20-30 in every 100 patients) will require a further procedure over 6-8 years to keep the stent working normally and prevent aneurysm rupture. After open surgery the risk of reintervention over the same time period is about 8-10%.

A recent editorial has drawn attention to the 3% ongoing annual failure rate for endovascular grafts. This is in addition to the annual rate of further intervention in conjunction with a need for lifelong follow-up. The author also highlights results from the Cleveland Clinic (a well known US vascular centre) where the results of endovascular grafting in large aneurysms were concerning with a 10% (1 in 10) 4 year risk of rupture for aneurysms 6.5cm in diameter or greater at the time of endovascular repair. In other words, even after apparently successful endovascular repair patients with large aneurysms still had a 1 in 10 chance of their aneurysm rupturing.

The long term durability of endovascular stenting is not known and it is not a risk free alternative to open surgery (Gorham TJ et al, 2004). A recent review article in the Journal of Vascular Surgery (Rutherford RB and Krupski WC, 2004) has concluded that in our present state of knowledge traditional open surgical repair is still to be preferred in younger patients at low operative risk - a view endorsed again in 2005 (Cronenwett JL, 2005). Increasingly this view is being challenged and in most current practice if a patient has an aneurysm suitable for endovascular repair then this treatment will be offered.

Endovascular stenting is here to

stay and in fact is the treatment of choice for 50-60% of all patients with

aneurysms in the USA (Nowygrod,

2006). Technology will continue to evolve and complication rates are likely to improve.

Endovascular stenting is here to

stay and in fact is the treatment of choice for 50-60% of all patients with

aneurysms in the USA (Nowygrod,

2006). Technology will continue to evolve and complication rates are likely to improve.

Patients who have undergone EVAR require lifelong follow up with imaging of their graft to detect problems at an early stage. This is usually by a combination of CT scan and ultrasound with angiography reserved for treating problems when they occur. Ultrasound is becoming the standard investigation but more research is required on optimal follow up regimes. One study has suggested that follow up may be targeted as most complications occur in patients who develop symptoms (Karthikesalingam A et al).

Laparoscopic aneurysm

repair

There are a few centres developing keyhole surgery for aortic aneurysm repair.

In principle this operation is the same as open surgery (see above). The

aneurysm is approached from the outside and a graft stitched into place.

It is different from the open operation because the incisions used in the

abdomen are much smaller.

It is not available as an option in most departments and only a few expert laparoscopic surgeons around the world are performing this procedure, although it does appear to be increasing in popularity. It will require considerable development if it is to become routine, but has the attraction of implanting the graft in a traditional way but without a large incision. This would combine the advantages of a minimally invasive and low trauma approach, with the durability and long term freedom from complications of an open repair.

Non-surgical treatments

The ultimate aim of some research is to slow or prevent aneurysm growth,

reducing or eliminating the need for surgery. There are no treatments

proven to reduce the need for aneurysm surgery but work continues. Beta

blockers, such as metoprolol or atenolol, may be helpful. A recent study (Hackam

DG et al, 2006) has reported that the use of angiotensin converting enzyme

inhibitor drugs (captopril for example) was associated with a reduced risk of

aneurysm rupture, but further studies are required.

Are there complications of treatment?

There are a number of potential problems that can occur after aortic aneurysm surgery. These fall into 2 main categories: generalised complications and local complications. Both types of complication can prolong the stay in hospital and may be fatal if they are severe enough. There is a risk of dying from open aneurysm surgery of between 3-7%.

Generalised complications

This means problems that can occur away from the site of the

operation. They occur because a major operation under general anaesthesia

has been performed usually with significant blood loss.

The commonest types of generalised complication usually occur in the heart or the lungs. They take the form of angina (chest pain), heart attacks and chest infections. In the majority of patients, especially those having a planned operation, these complications can be successfully treated. The combined presence of heart lung and kidney complications can result in the condition of multi-organ failure (MOF). This frequently fatal.

Another generalised complication that can occur with any operation is Deep Venous Thrombosis (DVT)

Local complications

This means problems related to the site of the operation.

The main early problem that can occur is bleeding at the place where the main artery has been joined to the artificial graft. This can be severe. The surgeon will stop all bleeding before completing your operation but sometimes further bleeding can develop during the recovery period - especially within the first 24 hours. If this happens the patient can require a further operation to control the bleeding.

Nerves controlling sexual function run very close to the aorta. Although attempts to preserve these nerves are usually made during an aneurysm repair they can be frequently damaged. In men this can lead to loss of erections. If erections are preserved, retrograde ejaculation can take place where the semen is ejected into the bladder due to inco-ordination of the various muscles. The effects of damage to the same nerves in women are not clear in the age group that usually require this operation.

Sometime after the operation, infection can develop in the artificial graft, although this is rare. If this does occur it can be a major problem and will probably lead to further surgery to fix the problem.

Occasionally replacement of the major artery in the abdomen can lead to impairment of the blood supply to part of the colon (colonic ischaemic). If this becomes very severe then further surgery can be necessary to remove the damaged colon and prevent further complications.

In approximately 20-30% of patients a weakness can develop in the scar on the tummy. If this happens it occurs months or even years after recovery from the original surgery. It can lead to bulging in the abdominal wound and the development of an incisional hernia. This seems to be more common in aneurysm patients and may require a further operation.

Endoleak is a complication virtually exclusive to endovascular aneurysm repair. The behaviour and management of different types of endoleak is becoming more clear cut with increased experience in this area.

What measures are taken to reduce complications?

To reduce the risk of DVT

Anti-embolic graduated compression stockings may be used, providing there is no evidence of hardening of the arteries in the

legs. Intermittent compression of the legs and/or feet using airbags is sometimes used in theatre to improve blood flow in the leg veins during the anaesthetic. Most

patients also receive heparin injections to reduce the risk of blood clots

forming. After your operation you will be encouraged to move around as

early as possible.

To reduce the risk of

infection

Antibiotics will be given at the start of the operation and sometimes for one or

two doses after the operation. Physiotherapy will be started shortly after

the operation to prevent secretions accumulating in the chest.

Aortic aneurysm screening programmes

As aneurysms can be a serious health issue much effort has been directed at trying to identify aneurysms before they rupture. Screening programmes have been used to detect patients with aortic aneurysms and to monitor the aneurysms if they are small. An aortic aneurysm will usually develop slowly and enlarge over a period of years. Surgery can be considered as the aneurysm enlarges. Although these screening programmes cannot prevent aortic aneurysms forming, they are able to reduce the chances of an aneurysm rupturing by treating it at an early stage.

The multicentre aneurysm screening study (MASS) funded by the UK Medical Research Council recuited 67,000 men aged 65-74 years. After 10 years of follow-up there was a 48% relative risk reduction in the risk of death from aneurysm rupture in the patients screened with an ultrasound scan (absolute risk reduction 0.41%). A recent editorial in the British Journal of Surgery has called for the widespread introduction of aneurysm screening in the UK. The cost-effectiveness of aneurysm screening is comparable with other screening programmes (Thompson SG et al 2009) with a cost per life-year gained one third of the published cost per life year gained with breast cancer screening or colorectal cancer screening and one eighth the cost per life-year saved with cervical cancer screening. However there is debate on whether screening is cost effective (Ehlers et al 2009). In the UK the national screening body is gradually rolling out screening across England. All men will be invited for screening when they turn 65years old.

Screening studies target men because aortic aneurysms affect men much more commonly. There is some evidence that screening for women may also be cost effective because of their longer life expectancy and increased risk of rupture (Wahhainen A, 2006). Aneurysms in women, when they do occur, seem to enlarge slightly faster than in men (Mofidi R et al, 2007).

Bengtsson H, Bergqvist D, Sternby NH. Increasing prevalence of abdominal

aortic aneurysms. A necropsy study. Eur J Surg 1992; 158: 19-23.

Sayers RD. Aortic

aneurysms, inflammatory pathways and nitric oxide. Ann Roy Coll Surg Eng 2002;

84: 239-246.

Rossak JI, Sporle A, Birks

CL, van Rij AM. Abdominal aortic aneurysms in the New Zealand Maori

population. Brit J Surg 2003; 90: 1361-1366.

Filipovic M, Goldacre MJ,

Roberts SE et al. Trends in mortality and hospital admission rates for

abdominal aortic aneurysm in England and Wales, 1979-1999. Brit J Surg 2005; 92:

968-975.

Powell JT.

Familial clustering of abdominal aortic aneurysm - smoke signals, but no culprit

genes. Brit J Surg 2003; 90: 1173-74.

Brown PM, Zelt DT, Sobolev B.

The risk of rupture in untreated aneurysms: the impact of size, gender and

expansion rate. J Vasc Surg 2003; 37: 280-284.

UK Small Aneurysm Trial

Participants. Final 12-year follow-up of surgery versus surveillance

in the UK small aneurysm trial. Brit J Surg; 94: 702-708.

Schlosser FJV, Tangelder MJD, Verhagen HJM et al. Growth predictors and prognosis of small abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg 2008; 47: 1127-33.

The Multicentre

Aneurysm Screening Study Group (MASS) into the effect of abdominal aortic

aneurysm screening on mortality in men: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet

2002; 360: 1531-1539.

Beard JD. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm. Brit J Surg 2003; 90:

515-516.

Thompson SG et al Screening men for abdominal aortic aneurysm: 10 year mortality and cost effectiveness results from the randomised Multicentre Aneurysm Screening Study. Brit Med J 2009; 338: 1538-1541.

Greenhalgh RM. National screening programme for aortic aneurysm. Brit Med J;

2004: 1087-88.

Lederle FA et al. Immediate repair compared with surveillance of small

abdominal aortic aneurysms. N Engl J Med 2002; 346: 1437-44.

Ehlers L et al. Analysis of cost effectiveness of screening Danish men aged 65 for abdominal aortic aneurysm. Brit Med J 2009; 338: 1542-1544.

Gorham TJ, Taylor J, Raptis S.

Endovascular treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Brit J Surg 2004; 91:

815-827.

Rutherford RB and Krupski WC.

Current status of open versus endovascular stent-graft repair of abdominal

aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg 2004; 39(5): 1129-1139.

Cronenwett

JL. Endovascular aneurysm repair: important mid-term results. Lancet 2005;

365: 2156-58.

Prinssen M, Verhoeven ELG,

Buth J et al. A randomised trial comparing conventional and endovascular

repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms. New Engl J Med 2004; 351: 1607-18.

Greenhalgh

RM, Brown LC, Kwong GP, Powell JT, Thompson SG. Comparison of endovascular

aneurysm repair with open repair in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm

(EVAR trial 1), 30 day operative mortality results: randomised controlled trial.

Lancet 2004; 364: 843-8.

Blankensteijn JD, de

Jong SECA, Prinssen M et al. Two-year outcomes after conventional or

endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms. N Engl J Med 2005; 352:

2398-405.

Evar Trial Participants.

Endovascular aneurysm repair versus open repair in patients with abdominal

aortic aneurysm (EVAR-1): randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2005; 365:

2179-86.

De Bruin JL Baas AF, Buth J et al. Long term outcome of open or endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm. N Engl J Med 2010; 362: 1881-9.

The United Kingdom EVAR Trial Investigators.The United Kingdom EVAR Trial Investigators. Endovascular versus Open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm. N Engl J Med 2010; 362: 1863-71.

The United Kingdom EVAR Trial Investigators. Endovascular repair of aortic aneurysm in patients physically ineligible for open repair. N Engl J Med 2010; 362: 1872-80.

Karthikesalingam A, Holt PJE, Hinchcliffe RJ et al. Risk of reintervention after endovascular aortic aneurysm repair. Brit J Surg 2010; 97: 657-663.

Moore WS, Matsumura JS, Makaroun MS, Katzen BT, Deaton DH, Decker M, Walker G.

Five year interim comparison of the Guidant bifurcated endograft with open

repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg 2003; 38: 46-55.

Lindholt JS, Juul S,

Fasting H, Hennegberg EW. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysms: single

centre randomised controlled trial. Brit Med J 2005; 330: 750-754.

Wanhainen A,

Lundkvist J, Bergqvist D, Bjorck M. Cost-effectiveness of screening women

for abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg 2006; 43: 908-914.

Mofidi R, Goldie VJ, Kelman J et

al. Influence of sex on expansion rate of abdominal aortic aneurysms.

Brit J Surg 2007; 94: 310-314.

Lederle FA.

Abdominal aortic aneurysm - open versus endovascular repair. New Engl J Med

2004; 351: 1677-79.

Hobo R,

Buth J. Secondary interventions following endovascular abdominal aortic

aneurysm repair using current endografts. A EUROSTAR report. J Vasc Surg 2006;

43: 896-902.

EVAR Trial Participants. Endovascular aneurysm repair and outcome in

patients unfit for open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Lancet 2005; 365:

2187-92.

Nowygrod R, Egorova N, Greco G

et al. Trends, complications, and mortality in peripheral vascular surgery.

J Vasc Surg 2006; 43: 205-216.

Hackam DG, Thiruchelvam D,

Redelmeier D. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and aortic rupture: a

population-based case-control study. Lancet 2006; 368: 659-65.

Last updated> 18 October, 2010